Many different types of leather are used in footwear these days. In this leather guide, we will also explain the many different styles of the same type of leather so allow me to break down the most common options and tell you a bit about each, sharing their pluses and minuses, the myths, and all of the other opinions I might have on each. There are, of course, many more types but in this leather guide, I will focus on the “main leathers,” so to speak.

The Dress Shoe Leather Guide

Calfskin Leather

Saying calfskin is like saying the word ‘car.’ It’s the general type of leather used to produce many of the subtypes, like ‘crust’ or ‘box’ (aka box calf, aka box ‘calfskin’ — see what I am saying?). It simply means that the leather came from a calf, as opposed to a full-grown cow (which in reality is the case for most of the leather used in the high-end shoe industry). Cow leather is simply not that great. Think about your 18-year-old skin versus your 60-year-old skin (no offense, but it’s a reality). That’s the difference between calfskin and cowskin.

In this leather guide, I will focus on the most common types of calfskins found in dress shoes, which are the following:

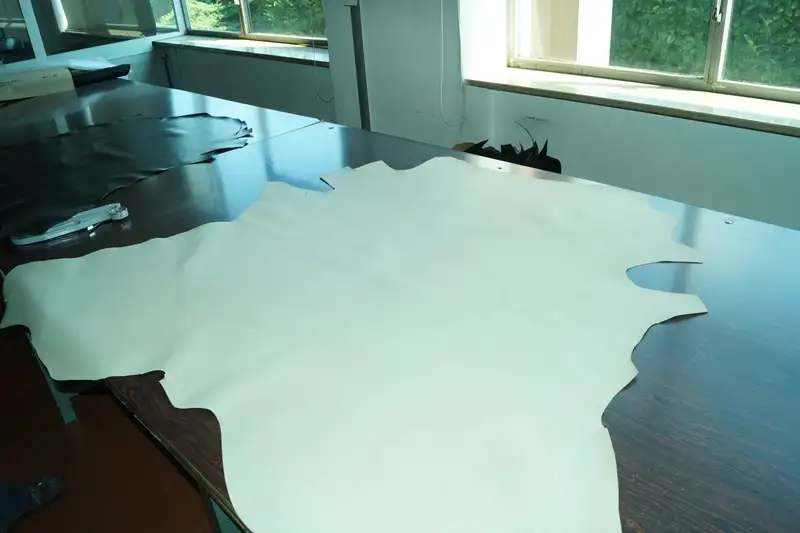

Crust Calfskin (Crust Calf Leather)

Crust calf is untreated (read as not dyed) leather. It is left intentionally natural in color to allow for a coloring process after the fact (i.e. not in the tannery, but rather by the shoe factory, a patina artist, or some other 3rd party). A lot of what is on offer these days is crust calf and that is because a lot of people want a patina/aged/burnished look and doing this on Crust calf is best and easiest.

The Italians and the French have been the ones to really pioneer the use of Crust calfskin with their history of colorful shoes. Crust calf, not having been in the drum for dyeing, is usually softer than the other types of Calfskins. However, in some cases, this softness can result in heavier creasing so do beware of that. Everything comes with a trade-off.

Because it is left untreated, it means that the leather’s defects (scars/scratches/bites, etc) are usually more prominent as they are not hidden by the dyeing process of the drums and finishing of the tanneries.

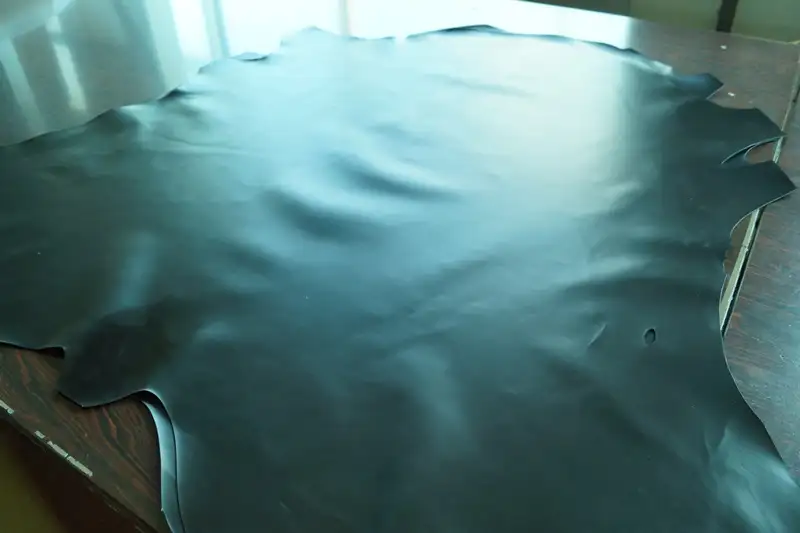

Box Calfskin (Box Calf Leather)

Box calf is the most traditional and commonly used leather. It is simply pre-dyed leather, like the majority of all black-calf leather. Most likely any shoe that has a uniform finish is going to be made from Box calf. The English shoemakers have traditionally stuck with Box calf as they never got so much into patina and making Green/Blue/Red shoes (although this is changing). Some notable tanneries producing Box calf are Weinheimer for Black calf, Du Puy, and Annonay for pretty much everything else. There are many more but these tanneries are among the most prestigious.

Box calf will always be stiffer due to the dyeing process of dyeing all the way through the leather. And Black box calf will traditionally be the most rigid. Something about the black dye makes it harder than the rest. For creasing, well this will depend on the quality of the skin as I have seen Box calf hardly crease at all and then some that crease worse than anything else. In this department, there is no true rhyme or reason. However, it is also generally thought of as being more resistant and durable than its crust counterpart.

Bookbinder Leather

This is somewhat of a contradiction in itself but it’s common in the industry so let’s discuss it in this leather guide. Bookbinder/Polished/Shined calf is simply a way to take cheaper leather and make it look more luxurious by applying an acrylic top coating that hides all blemishes. This coating leaves a shiny and plastic-like look.

Using a bookbinder leather allows the shoemaker to buy cheap and sell high, often misguiding customers into believing that it is top-quality calfskin when it is not. Italian brands have been doing this for years. Nearly all designer brands use this type of leather, and quite frequently as it is a great way to increase your profit margins. The lower-priced welted English brands have been using this too for quite some time although I presume that their ideas for doing so might be more functional for the following reasons.

Bookbinder leather is durable in the short term. Its top coating makes it nearly impenetrable. So if you live in a wet environment, then bookbinder leather can be a good option for you to not have your shoes so easily ruined or requiring constant upkeep. The downside is that it is extremely rigid which means it cracks easily, particularly in the vamp where the shoe creases during each step. And once it cracks, that’s it. There is no coming back from that. It also scuffs easily and you can’t shine those scuffs out as it is in the acrylic, not the leather.

Suede

Suede is leather. Don’t be mistaken. It’s the underside of the hide. For its long hair-like textured appearance, it has been loved and hated by many for years for various reasons. Let’s discuss the different types of suede and the pros and cons of each.

In this leather guide, I will focus simply on the ‘main suedes’. There are more options like Nubuck, Rough Out etc, which are less common. There is a link below that will explain more on those.

Full Grain Suede (reverse suede)

Full-grain suede is the premium part of suede that you typically find in high-end, expensive shoes. It is lightly sanded to maintain a beautiful uniform finish that often looks velvety. You can tell that suede is full grain when it is super soft and when you rub your fingers over it, it drastically changes from light to dark depending on which way the hair is lying. The hairs of the suede will be more prominent on full-grain suede. It will also have a shimmery sheen to it. The tighter grain that it has often makes it more durable, so to speak.

Split Grain Suede

Split suede is like bookbinder leather in a manner of speaking. They split the suede to create more pieces of it and thus utilize more for shoemaking. Split suede is cheaper and more often than not seen as inferior. Its texture is not nearly as plush as full-grain suede and does not have as much of a contrast between light and dark when rubbing your fingers across the suede. Its hairs are naturally shorter as it has been split and is generally not as robust as full-grain suede. It is therefore seen as more delicate. Most shoes you find in the industry use split-grain suede.

Shoegazing blog goes into a bit more technical detail on suedes, found in this article.

Here are a few of my opinions on the matter of suede and the differences between full grain and split suede. Split suede is often bad-mouthed but in reality, most makers are using it, and let me explain why. First of all, Full Grain is insanely expensive, nearly double (if not more) the cost of split suede. Of course, it is nicer to feel but it is not better in terms of durability (from my personal experience) and I believe that is why it is not used as much.

You don’t get double the lifespan from it and it is often more expensive than premium calfskins. It doesn’t age as well either as when those beautiful long hairs of the suede start to get worn down from wear and tear it simply does not look as nice anymore. It shows more of its wear and tear. Split suede on the other hand is not nearly as plush and elegant looking but it is durable and holds up well to wear and tear. At least the Repello suede from Charles Stead, which is what I have the most experience with.

I once wore my snuff (lighter brown) suede chukka boots (split suede) on a scooter in Paris and got caught in a hailstorm downpour. I got so wet that the shoes turned black. But when they dried, they dried just fine, evenly and the snuff went back to its original color. That’s the beauty of split suede. When it comes from a good tannery then its quality is still high and it wears very well.

On top of that, it takes rain better and this myth that suede isn’t good for rain is simply a myth, not based on fact. Cheap suede is not good for rain. Sand-colored suede might not be good for rain. But Snuff suede and darker colors take bad weather like a charm. In fact, I prefer to wear my suede shoes/boots on wet days rather than my calfskin leather. The only thing one must do is remember to steam and brush your suede once it has dried. Do that and you will forever have good suede.

Grained Leather

Grained leather is simply a stamped calfskin. Its look is not natural and is created by the tannery. You buy leather in different thicknesses when buying from the tannery and I want to say that grained leather is typically a touch thicker than your traditional calfskins as it needs to be when having that textured finish to it. You tend to find grained leathers on models that are more for adverse weather as its textured finish usually hides wear and tear better than a smooth surface does.

In this leather guide, we will focus on the more notable grained leather styles you will find in the dress shoe industry. But there are infinite styles of ‘grained leather’ out there, especially when going into lower-end shoes as grained leather is one way to hide blemishes on inferior leather.

Pebble Grain Leather

This type of grain (shown above) is quite prominent and is often used on boots and/or shoe models like full brogues. This is the grain that really takes the weather well as its thick pebble-like finish allows for the ultimate beat-up without showing too much wear and tear. The English shoemakers are quite fond of using this type of grain to combat that rainy environment, particularly for those who live in the countryside, want to dress smart and maintain a good pair of shoes. A country brogue or boot is nearly always grained, especially when coming from an English shoemaker.

Some notable pebble grains are Country Calf by Tannery Annonay and Scotchgrain by Tannery Weinheimer.

Pin Grain Leather

Somewhat like the pebble grain in look, the pin grain is simply a much smaller design of grain, that looks like it could have been made by pin dots. For some reason, its finish is often shinier and I never knew why whereas pebble is always matte. You tend to find pin grain in the higher end shoemakers as it is more fine grain. But it’s nice for having something different than calfskin and still being able to maintain elegance through its subtle appearance.

Sadly, I don’t find it holds up as well to adverse weather as the pebble grain options.

Hatch Grain Leather

This grain (shown below) has taken the industry by storm in the last 10 years. It’s a softer grain all around and much more subtle than its pebble-like counterparts. Due to this softer nature, I personally find it more dressy or at least the ability to wear it with more dress attire. On the contrary, I see pebble grain as casual, and hence why you often find that on boots or full brogues.

But, as of late, Hatch grain is found on all types of shoe models, even smart oxfords or dressy loafers. It’s the new-age grain that many customers seek but that is still somewhat rare to find as it has not fully caught on to being always on offer by all of the tanneries. The only downside is that I don’t believe this grain takes as much wear and tear as the others do.

There are many more variants of leather used in the industry, like Cordovan and a million other types of grain, but the ones in this Leather Guide make up the majority of what is found on the dress shoes of today.

Knowing the differences will help you make informed decisions about your purchases.

If you have enjoyed this Leather Guide post, please make sure to check out my other Educational Posts.

—Justin FitzPatrick, The Shoe Snob

Shop · Marketplace · J.FitzPatrick · Patreon

Excellent post, I was always wondering the difference between Box calf and crust calf and analine and vegetable tanned leathers.

Split and full suedes, this article goes along well with another article of yours from a bit back where you had diagrams showing the various thicknesses of leathers.

Cheers

Justin,

It is very nice of your to take your valuable time and provide us with this level of detail vis-a-vis the type of leather used for what shoe type.

Thank you so much for such an incredibly useful guide to the world of leather 🙂 I love beautiful calf leather but because of wet climate and snowy winters I also find hated bookbinder to be quite useful and intentionally I bought several of those shoes from low price (but goodyear welted) factory.

I have a few questions on bookbinder leather and have no idea who can be wise enough to help me with them. I hope that you are the right source of good knowledge on leather industry, so:

1/ Is there any difference between bookbinder leather and patent leather despite of shine degree? Both seems to be leathers with varnish/lacquer/acrylic coating.

2/ Are patent leather cleaners safe to use for bookbinder? I do have some experience with using Saphir Vernis Rife on bookbinder and it seems fine but still not sure with effect in longer period of time.

PS: Sorry if my text is weard but english is not my native language. I understand everything but only write or speak from time to time.

Cheers:)

Glad that you enjoyed the post Kamil. As per your questions, please below

1. Exactly as you said.

2. To be honest, I do not own either and have never used said product. But I imagine as they are a like finish it should be fine

I hope that this helps and your English was just fine

Thank you for that response 🙂 I try to keep calm 🙂

PS: Maybe I’m worrying too much about shoes but that attitude plus your blog help me not to ruin for example some nice crust leather 🙂 I guess, better safe than sorry 🙂

My pleasure and thank you for sharing Kamil!

Great summary, thank you Justin. I’ve purchased (and returned) a few shoes clearly made with bookbinder leather when I was first dipping my toe is finer shoes. It’s amazing how the cost is similar to stronger-quality shoes, but the quality just isn’t there with bookbinder. Fortunately, when I first tried them on they immediately started to crack, and I was fortunate enough to return them and learnt my lesson. Hopefully this summary will help others avoid the same issue.

Great article as always, Justin.

Well, I’d like to ask a question regarding the Leather’s stiffness

How stiff should leather be for shoes upper material?

First off, thanks for your articles and all the info.

I’ve read many descriptions of the types of leather but none that talk about the different quality levels. What makes the leather the Voss or Cleverly use better than the leather from Loake or Grant Stone? They all say they use the finest box calf but there has to be a difference. I know I have some shoes that are stiff and others that are suple and soft and don’t crease. What does it mean to use the finest Italian leather? There really isn’t any kind of scale I can compare manufacturers or models against.

Sorry for the late reply here. Only just found a spam folder with a lot of messages in it which for a reason I dont understand. You can buy leathers in different thickness. Someone also use more stiffeners/backers between the leather and the lining. These things will help/hurt flexibility, softness, pliability etc

very interesting your article, congratulations, also I wanted to ask you if there is a shop in London where are these types of leather? thank you very much

The author says “calf skin is like saying car. There are many different types of calf skin”. Then lists only 3 types. 3 types is not many types.

Excellent Article, Justin!

Thank you Joshua!

Justin, curious what your experience has been with pin grain since you wrote the article a couple of years back. I see that your brand offers a rugge boot (Colville) in this leather. I’m considering an MTO using pin grain leather hence my question.

Hey Faisal, it has worked great for me. It is softer than most grains. I like that it is more subtle.

Hi Justin, thanks for another honest blog. I was actually thinking of buying a pair of Barker Bailey, simply because I like the hand painted effect (im usually in the, Trickers, Cheaney, C&J price range) but I would like to know if these type of hand painted crust leathers are easy to care for, ie, what to polish them with etc.

Thanks in advance Justin.

Mark.

Hey Mark, thank you for the kind words and support. Yes, ‘patina’ style shoes are easy to care for like any other shoe. At the end of they day, they are still dyed leather just dyed by hand and not by the drum in the tannery. They will be more susceptible to harsh weather but also easy to accept re-coloring from cream polish and take a nice shine. It is slightly more advanced than working with box calf, but also more enjoyable at the end of the day with more character in the leather

Justin,

a comment to your statement regarding bookbinder Calf,

an alternative reason for using it could simply be the thickness

availability below 1 mm, which could be hard for some Makers

to find today. I have no experience with bookbinders leather.

Thank you for sharing JP

Thanks for the education.

always happy to help 🙂

Can you comment on the use of chrome tanned leather on high end shoes please? I have read that most shoes are produced using chrome. The popular museum calf by Ilcea is chrome tanned, I have had little luck in finding veg tanned museum calf.

veg tanned is not often used for high end dress shoes upper as it doesn’t hold structure and it is highly absobent which means it stains.

Thank you

I wonder when makers switched to Chrome. Also I understand Chrome will not develop a natural patina.

Finally re crust leathers. Are those used as uppers Also Chrome tanned?