Goodyear Welted, Blake, Hand Welted, Norwegian, Bologna, Cemented & More

When it comes to high-quality footwear, the way a shoe is made is just as important as how it looks. Yet many people still confuse—or completely overlook—the types of shoe construction that affect not only the durability and comfort of a shoe, but also how it fits, breaks in, and ages over time.

So, to help you understand what really goes on beneath the surface, I’ve put together this full guide to the most commonly used shoe constructions in both ready-to-wear and bespoke shoemaking. Whether you’re just getting into quality shoes or refining your collection, this guide will help you make smarter choices and appreciate the craft even more.

Table of contents

- Goodyear Welted, Blake, Hand Welted, Norwegian, Bologna, Cemented & More

- 1. Goodyear Welted

- 2. Hand Welted

- 3. Blake Construction

- 4. Blake Rapid Construction

- 5. Norwegian (Norvegese) Construction

- 6. Bologna (Sacchetto) Construction

- 7. Cemented Construction

- 8. Storm Welt Construction

- 9. Moccasin Construction

- 10. Strobel Construction

- Conclusion: Which Shoe Construction Is Right for You?

1. Goodyear Welted

Let’s start with the most respected shoe construction (on a production level) in classic men’s shoes: Goodyear welted.

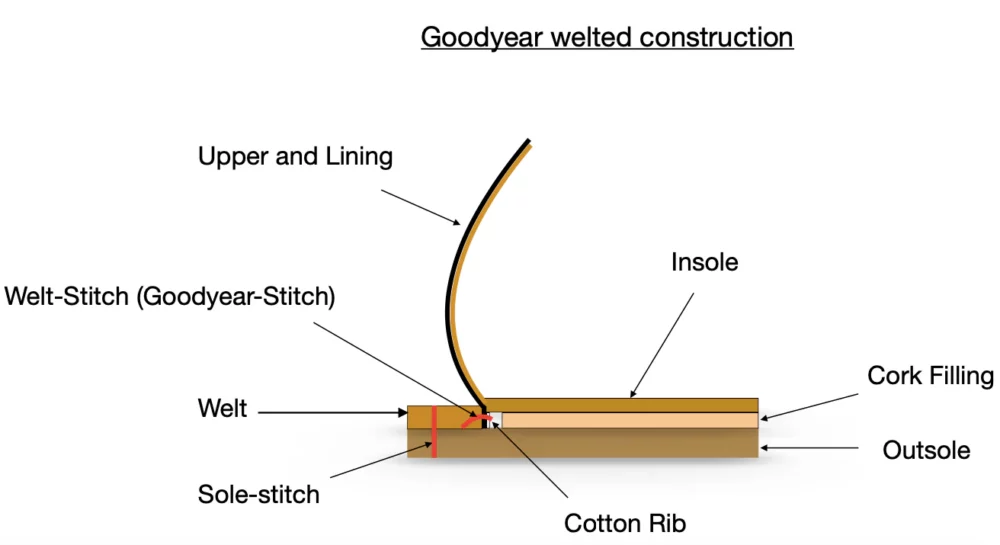

This is the bread and butter of traditional English shoemaking and is regarded as the gold standard for durability, structure, and repairability. The welt—a strip of leather—is stitched to both the upper and a canvas rib attached to the insole. The outsole is then stitched to the welt, rather than directly to the upper. The benefit? You get a relatively waterproof build, a cork-filled footbed that molds to your foot over time, and a shoe that can be resoled over and over again—often lasting decades if well cared for.

While Goodyear welted shoes are often associated with English craftsmanship, the method was actually invented by Charles Goodyear Jr., son of the American inventor who developed vulcanized rubber. It is also becoming more common for a new brand to offer Goodyear Welted construction than it was, say, 20 years ago, where most new brands were Blake Stitched.

If you’re looking for a pair of shoes that can age beautifully and be serviced over time, Goodyear welted is the sweet spot of traditional construction.

2. Hand Welted

Hand welted construction is, in many ways, the older and more labor-intensive brother of Goodyear welted.

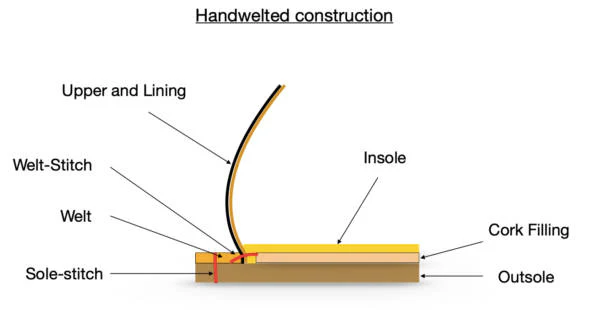

It follows a similar theory—stitching the welt to the upper and insole—but it’s all done by hand, without the use of a canvas rib. Instead, the shoemaker manually carves a feather from the insole, which the welt is stitched into directly. This allows for a thinner, more refined sole while still retaining excellent durability and repairability.

The use of the hand welted construction is most often found in bespoke or high-end shoes, and while it takes much longer to produce, the end result is usually cleaner, and often more elegant in execution. If you value artisanal craftsmanship and don’t mind paying for it, hand welted shoes are about as good as it gets.

Historically speaking, getting hand welted footwear was going to cost you extra money, but with the rise of Asian manufacturing, you are seeing hand welted options sub $500.

Of all the various types of shoe construction, Hand Welted is often regarded as the most prestigious.

3. Blake Construction

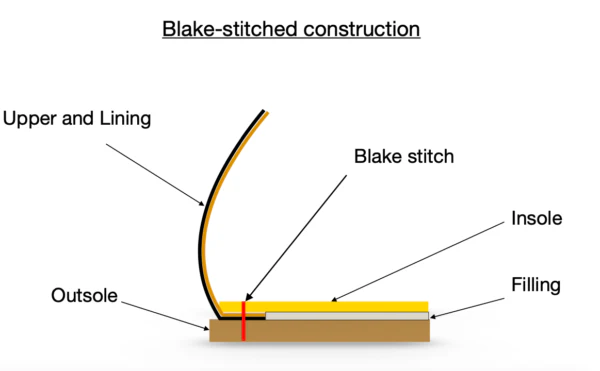

Blake construction is widely used in Italian shoemaking and is known for its sleek, lightweight feel. In this method, the outsole is stitched directly to the insole and upper. This creates a very flexible, close-cut profile—great for slim, elegant shoes.

The drawback? It’s not as waterproof or as easy to resole as Goodyear or hand welted shoes. Also, since the stitching goes through the entire shoe, it can be more vulnerable to moisture seeping in. You’ll also find fewer cobblers equipped to resole them, especially if they don’t have a Blake machine.

Still, a well-made Blake shoe has its place, especially for warm weather or more refined silhouettes where flexibility and lightness are priorities.

4. Blake Rapid Construction

Blake Rapid is essentially Blake with a twist. Instead of stitching the outsole directly to the insole, there’s a midsole involved, which the outsole is then stitched to. This adds an extra layer of durability, slightly more cushion, and allows for easier resoling compared to standard Blake.

Some say a well-made Blake Rapid shoe can rival a Goodyear welted one. And while that might be true on paper, personally, I still lean toward Goodyear construction—it’s what I’ve learned to make and appreciate the most. But that doesn’t mean Blake Rapid is inferior; it’s just different.

Of the various types of shoe construction, the Blake Rapid is probably among the least used. Most brands either go Blake or Goodyear.

5. Norwegian (Norvegese) Construction

Despite the name, Norwegian construction is another technique that’s often seen in Italian shoemaking. Originally developed for creating waterproof footwear, it features a distinctive wraparound welt that’s visible from the outside.

In its true form, the welt sits fully on the outside of the shoe, stitched flush with both the sole and the upper. This creates a rugged, weather-resistant build ideal for outdoor use. But today, Norwegian stitching is also used decoratively to give a shoe a bold, chunky look—even if it doesn’t offer true waterproofing.

If you want a shoe that looks unique and stands up to the elements, this is a solid choice. But keep in mind: this construction tends to be heavier, stiffer, and costly.

6. Bologna (Sacchetto) Construction

Bologna construction, sometimes referred to as ‘Sacchetto (bag),’ is all about comfort. Commonly found in Italian loafers and lightweight dress shoes, this method involves wrapping the lining into a sock-like shape and stitching it to the upper, eliminating the need for a traditional insole.

The result is a super flexible, slipper-like feel. It’s not as durable or supportive as welted construction, but for soft, elegant footwear—especially for indoor or light use—it’s incredibly comfortable.

Just don’t expect it to last you 15 years. This is luxury in the moment, not longevity.

7. Cemented Construction

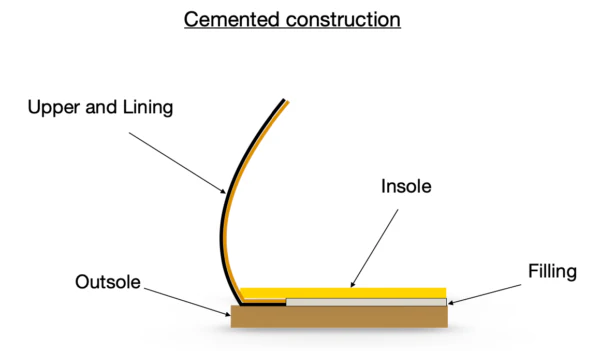

Cemented (aka glued) construction is the most cost-effective method in the industry. The outsole is simply glued to the upper, which makes it fast, cheap, and lightweight—but also disposable.

This is the construction you’ll find in most fast-fashion shoes. Once the sole wears down or separates, it’s game over. There’s no real way to repair it, and the upper tends to wear out just as fast.

I’d only recommend cemented construction for shoes you don’t plan to wear often, or when you need something quick and affordable. It has its place—but it’s not in your rotation of long-term staples.

Of all of the types of shoe constructions, the cemented method is the most prevalent as it is the cheapest.

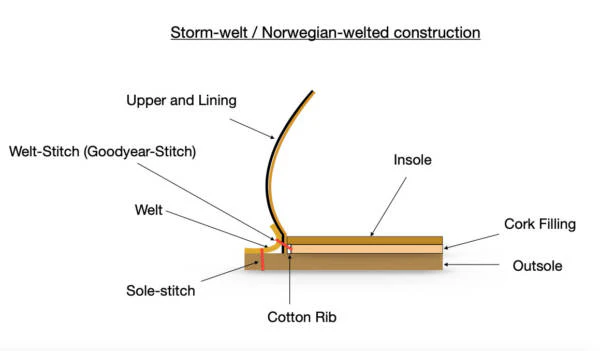

8. Storm Welt Construction

Storm welt is a variation of Goodyear construction that adds a raised lip or flap of leather running along the perimeter of the shoe, where the upper meets the sole. It’s designed to provide extra water resistance and protection from the elements.

You’ll most often see this used in country boots or heavy-duty footwear—basically anything that needs to hold up in rougher weather. The look is chunkier and more rugged, which some people love (and others avoid).

Functionally, it’s one of the best options for wet climates or winter use.

9. Moccasin Construction

Often found in boat shoes, driving loafers, and casual slip-ons, moccasin construction wraps the upper leather underneath the foot and stitches it along the top of the vamp. This creates an extremely soft, unstructured, and flexible shoe.

It’s great for comfort and laid-back style, but lacks the support and longevity of structured builds. Best saved for summer wear or light, casual use.

10. Strobel Construction

Common in sneakers and modern casual footwear, Strobel construction involves stitching a textile insole directly to the upper, then gluing the outsole on afterward. It’s efficient and lightweight but designed purely for function—there’s nothing traditional or long-lasting about it.

Still, it allows sneakers to stay flexible and breathable, which is why it’s become the industry standard for athletic and performance shoes.

Conclusion: Which Shoe Construction Is Right for You?

Choosing the right shoe isn’t just about style—it’s about how the shoe is built to support you over time. Whether you prioritize comfort, longevity, weather protection, or elegance, there’s a construction method that fits your needs.

If you’re looking for versatility and long-term value, Goodyear welted is hard to beat. Want something soft and elegant? Bologna is worth a try. Need a rugged winter boot? Storm Welt or Norwegian has you covered.

The more you understand these types of shoe construction, the more confident you’ll feel building a wardrobe that’s both stylish and built to last.

—Justin FitzPatrick, The Shoe Snob

Shop · Marketplace · J.FitzPatrick · Patreon

Great writeup. Although i miss a little on the st. crispin construction. What can you tell about that?

Great writeup. Although i miss a little on the st. crispin construction. What can you tell about that?

Personally, I’ve always loved the look of a sleek Italian loafer more than the robustness of a proper British Goodyear-welted brogue or penny.

I know that any sudden gust of rain would quickly destroy the delicate works of art but damn if they don’t make my broad ugly feet look slightly elegant.

I’m not sure sure how true it is, but I feel that a Blake constructed shoe allows my EEEE feet more flexibility to wiggle and breathe than a Goodyear-welted one. I won’t be surprised though, as Blake construction allows for far more bend (not that it’s a good thing) than a Goodyear-welt.

i think you will find that the major advantage of the goodyear or norwegian methods is that each stitch holding the welt also pulls the upper tightly around the last for a superior fit.

Dron – Thanks. I had never heard of the St. Crispin construction before. After researching for a little while, I dug up this:

http://www.comfortshoes24.co.uk/baer-craftsmanship/traditional-techniques/die-san-crispino-machart.html

It would seem that this construction is mainly for comfort walking shoes, which is why I would not be familiar with it, as I generally stick to dress shoe constructions.

Benjy – I understand your sentiment. A goodyear welted shoe is definitely going to be a little bit broader and when adding that to already wide feet, it certainly does not help for trying to appear slim.

Theo – I have never thought of that before nor heard it either, but I can definitely see what you mean and agree with it. Thanks for the input.

-Justin, “The Shoe Snob”

Thank you for the help, justin.

I own a pair dress/fashion boots with that construction so I thought there were more to it, but I guess in this case it was chosen for the aestethics only. They do look good though. IMHO

Thank you for the help, justin.

I own a pair dress/fashion boots with that construction so I thought there were more to it, but I guess in this case it was chosen for the aestethics only. They do look good though. IMHO

Dron – No worries my friend!!

-Justin, “The Shoe Snob”

Thank you very much for your intresting blog. I am from Russia and i find here so usefull infirmation.

I have some question about Goodyear Welted technology. Could you please explain how the upper leather conect with insole?

Natty – Sorry for this late reply, I was having troubles with my comments for a few days. The way that you connect the upper leather to the insole is through the welt. What you do is create a wall (or feather within the insole) that you then affix the welt to while at the same time poking a hole through the insole (wall), welt and upper leather to attach them all together. It’s hard to explain but if you look at the pictures carefully you should be able to understand it. If not, then go to Carreducker’s blog, on the right side of my page and search for a point in which they are showing this. Hope that this helps.

-Justin

With all due respect, I think you are mistaken about Goodyear construction being the choice of many (if any) bespoke makers.

Handwelted (a direct welt to upper to insole connection is the preferred method among almost every bespoke maker I know of or am familiar with. Carreducker–handwelted, Delos–handwelted, Lobbs, St James–handwelted, G&G bespoke–handwelted AFAIK.

Goodyear construction involves gluing a canvas rib (gemming) to a generally inexpensive insole…sometimes not even leather. A machine sews the welt, and upper to canvas ribbing but fundamentally, the binding principle is entirely dependent on the glue holding the gemming in place.

It makes no sense for a bespoke maker to hand inseam to a glued-on canvas rib when the same technique–inseaming directly to a high quality leather insole–will give vastly superior results.

DWFII – I did not know that you read the blog, but glad to see you on here. I think that I was slipping up with my words, since I have made shoes before entirely by hand, being naive to the fact that the term ‘goodyear’ strictly referred to machine made. I was under the impression, for some unknown reason, that goodyear referred to the use of a welt and the way that it was attached not thinking that doing it by hand, was not referred in the same way but actually just called hand welted. Therefore, you are right, of course, but I just misused the wording and do not think that bespoke makers used canvas ribs. What you stated is evidently obvious, especially when you explain it. It makes no sense to use a canvas rib only to then stitch by hand. But I am glad that you commented in order to point that out for this post and future reference, so I do not make the mistake again.

-Justin

Dear Anon – Hopefully you get this answer as I accidentally deleted your comment while trying to publish it (on my small phone…). Any to answer your question, best to start with neutral. However some threads are stain proof, in the sense that no matter what, they will not change color no matter what you use to polish them….best to test this on the inside heel as it’s the most inconspicuous part of the shoe…hope that this helps..

-Justin

some but few high end goodyear welted shoes do not use a canvas rib but a channel chiselled out of the insole as for hand welted

You are not a snob, just a prat.

Please stop blogging.

omg, you are so right. I think that due to your infinitely sage advice I will stop blogging and thus stop providing the useful and insightful information that many of my readers come to obtain on my site. Because why else would I not listen to someone called “fed up with your shit,” I would be foolish not to…….. seriously, get a life man!

yes, you are right…but they are very few…

I think the discussion on Norwegian welt is a bit light- it actually is as good, if not better than the Goodyear welt. I’ve got a pair of fabiano hiking boots bought in 1978 that are still going strong – would never trade for anything else. goodyear is great on my Aldens, more refined looking, and works great- but I think the Norwegian is superior in any outdoor and work boot situation

you are right, in any outdoor situation, it is far superior than just a GY welt..

does anyone have any references from journals about footwear construction???

That was a very clear explanation. It helped me understand more about why I would pay a lot of money for a pair of shoes. I’ve been buying SAS. I live in a small city and that is the best we have here, but I realize there are other brands out there.

glad that you enjoyed it Louis

Thx for your explanation of the Norwegian and Goodyear soles. I am seeking a pair of backpacking boots. This is helpful information. I have a requirement for an orthotic lift and am seeking manufacturers making a product that I might have adjusted for my need. Decades ago I had purchased a pair of Raichle hiking boots and these were very comfortable and were modified for me to wear. should anyone have info regarding a modern backpacking boot which allows the lift to be built up on the outside, I would be very grateful. I hope to be backpacking later this summer. Thx in advance.

Did you ever find someone? I’m in the same predicament.

hi there, I am doing some pereonal research on hiking boots and shoes and was just reading about the Peter Limmer boots and I think they do custom made hiking boots, you might want to check them out.

Easy to understand! I was just looking for a clear explanation. What about the Sacchetto Bologna construction? I am new at this topic and I get confused between the Blake rapid and the Sacchetto Bologna. Can you please mention some differences between this two styles of construction. Thank you!!

my son is a big man – 6’4″ and about 250 pounds. I am interested in getting the Pikolinos shoes for him, but am afraid the shoes aren’t sturdy enough for his size. They are a good leather and seem to have a good stitch – do you know anything about that shoe and if it would be good for a big man?

Hello, I have a few pairs of shoes that fit to tight that are size 12/and a half. Being a shoemaker reconstruct the shoes by putting on a size 14 sole and making them into a D width. The right shoe needs to have a High Toe Box the shoes are a Black&White Suede and another pair of Blue&Gray Suede with a High Toe Box. Reconstruct them into 14 D.

I have no clue what you are asking or saying, to be quite honest. Sorry. Is it a question or a statement?

A dang fine overview of the majority of men’s shoe construction. I’m really only interested in Goodyear welted constructed foot wear (with the exception of deck/boat shoes, of course :-)) as it suits my budget (I can’t afford hand-welted/bespoke shoes) and I love getting a shoe re-soled if I love wearing it!

It’s interesting reading the comments here: only one ‘person’ has taken the time to ‘construct’ a shi*ty comment…I’d say it’s of the ‘cemented’ variety 😉

Best to you, Justin.

Regards

Tony

Thank you Anthony, I am glad that you enjoyed it! And yes, there are always someone who needs to construct negativity