With the influx of Spanish private labeling (factories making for other brands) and Latin American shoemakers (Mexico, Argentina, Colombia etc), I am starting to see a lot of questions/complaints about the shoe welt joining on Goodyear welted footwear. Before Instagram and Facebook, I felt like the shoe world might have been a lot simpler. But at the same time, that simplicity also caused a lot of misunderstandings about the reality of shoemaking. I will use America as the example here as I believe most of these misconceptions start here being one of the largest consumer markets for dress shoes.

Before globalization became a thing and we all just shopped at our local mall, most of what you found at the high-end American department stores (which were your only point of sourcing fine dress shoes) were Italian dress shoes. The reality is that 20 years ago, Blake Stitched shoes ruled the marketplace in the US, and really still do.

Your average person has no clue what a shoe welt joining is. Nor do they even know what Goodyear welted is. But they know Italian shoe finishing because chances are they have seen it in a Santoni or Ferragamo shoe. Italian shoe finishing is often flawless mainly because it is all Blake Construction, which has no welt. Since they have no welt, there is a flawless look at where the heel is met by the sole. So, people used to seeing those types of shoes get freaked out when they see what looks like a cut in the sole (really the welt). Many go online and start panicking that their shoe is flawed. Well, it is not. Not even close.

So, let’s explain what a welt is and how it is applied to your shoe.

A welt is a strip of leather sewn to the insole and upper (and later sewn to the sole) that can either go all of the way around the shoe (360-degree welt) or in the case of most high-end Goodyear welted shoes, usually goes from joint to joint (270-degree welt). Now, you will imagine that this welt has two ends and those ends need to meet somewhere and/or be connected to a different piece of leather (known as the rand – see video below).

When cutting those ends to be joined it is usually cut at a 45-degree angle, not a vertical one. The other piece of leather (or end of the welt) is also cut at that same angle so they join together as neatly as possible. When these two pieces join, you get an obvious line that signifies their meeting. If these angles are not cut perfectly, you start to get more untidy-looking shoe welt joinings.

These shoe welt joinings can be later manipulated (tidied up) by the person who trims the sole as well as the finishing department. That level of ‘finishing’ is what starts to separate different degrees of craftmanship, countries of origin, and price points. One of the main reasons you are paying for expensive footwear is the capability of clean finishing. The higher you go in price, usually the tidier the finishing is.

When you look at handmade shoes by Japanese bespoke shoemaking you would be hard-pressed to find any indications of a cut, slit, joining, etc. as they are the masters of finishing and value perfection. But it is the opposite when it comes to a lot of Spanish shoemakers and even more so South American shoemaking. It is simply not what they value. Their intentions are to make solid shoes for a solid price, not to make you the best shoe in the world for under $400. That doesn’t exist. And they are also in the market of utilizing all of the materials possible. Not creating waste that most of the high-end makers do, and charge you for.

Believe that a lot of what you pay for in high-end Goodyear welted shoes is wastage.

What piqued my interest in writing this post, was a gentleman (@theshoeenthusiast on IG) who shared the shoe welt joining of one of his Goodyear welted Mexican Made boots by Taylor Stitch on a Facebook forum, asking if what he noticed was ‘normal’ or ‘acceptable’. He felt its look indicated a flaw and asked for guidance. His way of going about it was more honorable because most forum-type individuals immediately go on there and start bad-mouthing the company/shoemaking skills, and looking for a moral pat on the back, all while not having a clue about anything nor the people agreeing.

Now, there were some commentators there that were automatically spewing nonsense but thankfully one very well-respected and knowledgable cobbler helped shed light on the realities of shoemaking. Now the OP (original poster) I believe understood after hearing the cobbler’s opinion and learned about it and I felt that this topic needed some exposure as we will see more and more of this issue and we should be all prepared for that.

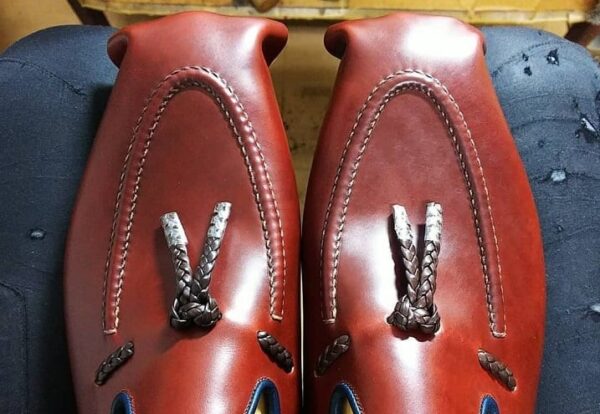

The reality is that welt leather is made in very long, almost endless strips. Just look at the picture above. Therefore, it has to be spliced. Now, imagine, this is not a perfect robot-like situation as shoe sizes vary which means that welt splices will too. They are not always cut with Samurai-Sword precision and sometimes are unkempt looking. When you get shoes from certain countries, they are not there to tidy that up to look like your fine Gaziano & Girling style of shoemaking. It’s simply not what you are paying for.

Sometimes the shoe welt joining is simply not that nice looking. But that does not mean it is flawed, in error, bad quality, or any of that nonsense. It just means that you are paying for a solid shoe and not flawless finishing. In extreme cases, that welt splicing will require more than one per shoe/boot, as is the case with the boot in question. You can see this in the photos above where they spliced the joint as well as the toe. This is nearly unheard of in European making, but according to one poster in this photo comment, has been seen many times in shoes coming out of Leon, Mexico. And more likely than not, it is because they are not there creating wastage. They are there to use all of the materials possible.

In 10 pairs, I imagine maybe 1 or 2 will come out like this. And if you happen to receive those pairs, it simply makes you unfortunate, but not justified in claiming flaws or asking for paid returns. If all shoes were always flawless we would have no distinction in prices. Yet we do, and most often this is due to the cost of labor and time spent on said labor because leather stays pretty constant across the board.

When you see things like this, especially when you are buying shoes from a country not known for providing flawless finishing, then manage those expectations because if something is structurally sound yet simply not flawlessly attractive, it does not make it at fault. I won’t lie. It is not pretty at all. But I would never ‘not expect’ that from shoes made in Mexico. That is also not a knock on Mexican shoemaking. That is because my expectations of their values in shoemaking are realistic. Until they change their own values, this won’t change.

We buy shoes to be worn, not to put on mantlepieces. More often than not, we do more damage on our first outing than anything we moan about when unboxing them. So next time you buy a pair of shoes from some new brand that is making the shoes out of some country not rooted in flawless finishing, bear that in mind when critiquing it. We must continue to manage our expectations as consumers as constantly expecting perfection is a fool’s game.

Here, below, you can see a selection of shoe welt joining from my own brand. I intentionally tried to find ones more unkempt as it happens. The reality is that the majority look like the above pair but even the Spanish often leave this untidy and with divots and bad joining. It’s a part of what makes Spanish shoes more favorable in price. That is the reality of shoemaking. More time spent perfecting details equals higher pricing. It’s simple math.

—Justin FitzPatrick, The Shoe Snob

Shop · Marketplace · J.FitzPatrick · Patreon

Very informative. I have always thought that quality welted shoes had the 360 degree welt – didn’t know that some quality shoes are made with 270 degree welts.

Most quality shoes are 270

most proper dress shoes use 270 welts. They almost only do 360 when adding a stormwelt or norwegian welt. 360 welts are too heavy for luxurious looks

well i was going to ask why not avoid the issue by doing a 360 welt. From your reply do I understand that the rand is not as thick as the welt making it less heavy, and why would an additional 90 degrees really make the shoe heavy. Thank you.

Thank you once again for shedding light and clarity on a subject too many just rant about without understanding or proper knowledge. And especially so to explain what to expect from certain shoes, makers and the reasons why. Much needed and much appreciated.

my pleasure Mark, thank you for reading and for commenting.

Hola amigo, me gustaría compartir mis conocimientos en diseño, modelaje y fabricación de calzado. Tengo escuela italiana y treinta años de experiencia. Si gustas ver mi trabajo solamente solicita mi portafolio o vídeos de mis zapatos

Ripper article and thoroughly agree.

Thank you!

I am an exotic shoe enthusiast and own several pairs. I’m new to this blog and would love to have the exotic shoe conversation with anyone interested.

Those are some pretty tidy untidy “unkempt” welt joints!

Well written article Justin. Welt is critical part when done through machine or hand. And 1 in 10 might not have clean cut at end.

Problem is once welt is done, other end of the welt is done when whole shoe is welted. Now even if cut doesn’t come clean, we can’t discard the whole pair so there are few tricks done to make it work. I am sure someone selling shoe for 4000$ will discard, but not ones where the majority of market is.

And again, it’s cosmetic. It’s just the visual. It doesn’t affect the structural integrity or functionality of a shoe.

Also, if welting is done by machine or hand, final welt trimming is done by hand. So some variation in welt joint is expected and even considered part of handmade process.

Thanks Sandeep, glad that you enjoyed and thanks for sharing!

thanks alot sir.its very informative.